From the Rabbi

Often, we feel a little too “small” to fulfill our calling. In Parashat Vayikra, we’re reminded that even Moshe himself felt what we might now call As we prepare for Passover and celebrate Shabbat HaGadol, we read from the Prophet Malachi, who tells us that an essential part of liberation is a new spirit of love and understanding across the generations. What can we do this week to have a moment of intergenerational love and understanding?

Rabbi Ruhi Sophia is running in the World Zionist Congress elections! TBI urges support for the Hatikvah: Progressive Israel slate (Slate #16). Learn more and make your voice count by casting a vote.

Fear and Vision (Mar/Apr 2025)

Yirah: Fear and Vision

One of the things I love best about studying Torah is that, even thought the text is the same each year, I notice different things based on my own state of mind and the state of the world. This winter, since the beginning of the book of Exodus, I have been noticing the recurrence of the concept of yirah, which is often translated as “fear” or “awe.” The midwives are described as “fearing God” when they choose to defy Pharaoh’s order and kill the baby Israelite boy in Chapter 1 of Exodus. The Israelites are also described as “fearing God,” after they cross the Red Sea, right before they break into song. After receiving revelation, in chapter 20 of Exodus, the Israelites are again described, as “fearing God,” when they promise to keep the mitzvot.

I am intrigued by the Biblical model of yirah. The fear, such as it was, that the midwives felt was not one that made them cower, but one that enabled them to defy a king who had every power to kill them. The yirah that the Israelites felt at the sea inspired them to burst into song. The yirah they felt at Mt. Sinai encouraged them to embrace obligations.

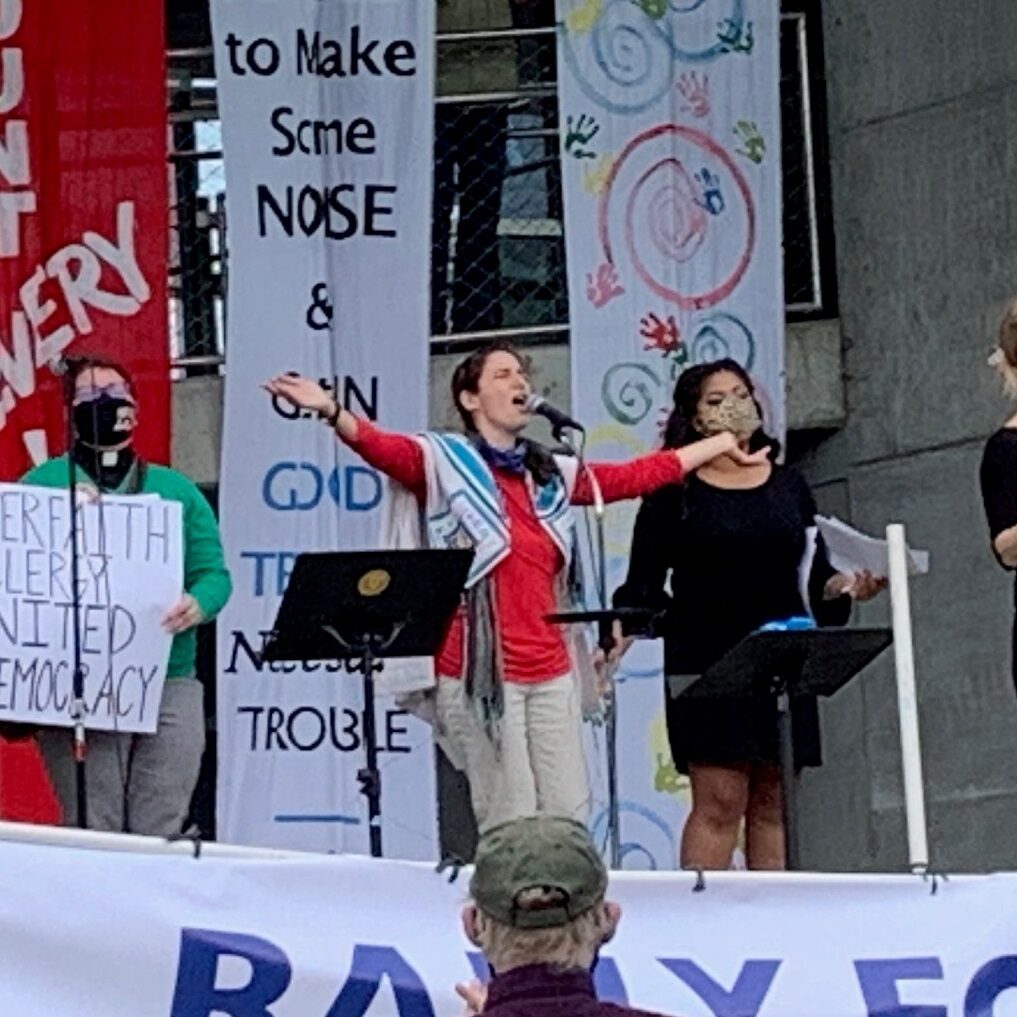

In this time, I have been trying to emulate that Biblical yirah in my own leadership of the congregation. I have been motivated by that yirah to expand my work not just within the synagogue, but also beyond the synagogue. I have been working with a small interfaith team to host the “Stronger Together” interfaith potlucks, which in the next two months will include attempts to begin organizing interfaith caucuses dealing with regional and national issues. I have been reaching out to more non-Christian clergy to invite them to join our interfaith group. I have brought my yirah to testifying at the County Commission for the rights of our trans and immigrant community members. And it is with great yirah that I have agreed to serve on the Hatikvah Slate in the World Zionist Congress elections this spring.

Perhaps yirah functions differently from how I often think about fear because it accesses not just fear of how terrible things could be if we act (or fail to act) in immoral ways, but also a positive vison of the beauty that we can create when we do take action. So if you’re feeling frightened, I encourage you to channel that fear into yirah: What vision do you want to protect? What support do you need to take action?

Purim: The Absurdity of Purim Today

Purim: The Absurdity of Purim Today

An unchecked ruler without any self-control and unlimited power lashes out at a woman who dares to assert her sexual agency. With the encouragement of his sycophants, he consoles himself by coercing more compliant sex slaves. Those in his retinue jockey for power, playing out their petty rivalries and slights without regard for who gets hurt.

In the end, no one wins — but as long as the Jews stay in the good graces of the king, we’re probably safe.

I wince at this synopsis of the Purim story because it feels too uncomfortably close to the dynamics playing out today with Jews in the United States.

As I write this, the current administration is rolling out the extreme agenda of Project 2025 (despite claiming not to). In parallel, the same authors conceived of Project Esther, “a strategy to combat antisemitism,” that seemingly did not consult with many actual Jews in the planning process. The strategy does not concern itself with the link between antisemitism and white nationalism, but it does coin a new phrase, “Hamas Support Network, (HSN).” HSN isn’t an actual organization, but a broad brush that ranges from Hamas to college students at Pro-Palestinian rallies. With this neat rhetorical sleight of hand, the Project Esther document claims that the HSN is “supported by activists and funders dedicated to destroying capitalism and democracy,” and that “the HSN benefits from the support and training of America’s overseas enemies.” We see Project Esther’s work playing out, suppressing free speech and even targeting Jewish organizations.

There are certainly kernels of truth in Project Esther’s claims. There were also kernels of truth in Haman’s claims about the Jews in chapter 3 of the book of Esther — the Jews did have a different language and different laws. Where both Haman’s claims and Project Esther’s claims break down, however, is in their creation of a monolithic enemy “other” threatening the safety of the nation. Haman had a king ready to do his bidding who was more interested in his own wealth and the obedience of his retainers than morality or truth. Project Esther will no doubt find its willing enablers in this administration.

The authors of this disingenuous plan write, “Today, Israel, Jews everywhere, and Americans face yet another ‘Haman.’ The question remains: Will we face the threat as Esther did so many centuries ago or capitulate to intimidation and fear?” While tradition sometimes tells us to get in a state of mind where we have trouble telling the difference between Haman and Mordechai, it doesn’t intend for us to have our moral compass inverted.

In actuality, Esther is an excellent model for a fake effort at Jewish liberation. As I think about the symbolism of Esther, I find it quite suggestive. Purim is an incomplete liberation, if a liberation at all. The final reason given in Megilla 14a for why Hallel (the joyous recitation of Psalms 113-118 on holidays) is not recited on Purim, is that we cannot recite “Give praise, o servants of Hashem” after the Purim salvation because we were, in fact, servants of Ahashverosh — even at the end. Esther saves her people not by standing up to a despotic king, but by seducing him. At the end of the story, she is still stuck in the harem of a pagan king, a capricious and dangerous one at that.

The Esther model seeks Jewish safety not by defying the status quo, the power structure, but by sucking up to it. It is safety without freedom. It is also a very assimilated sort of safety — Esther successfully hid that she was Jewish in the court of Achashverosh, which suggests that she wasn’t making any demands about kashrut, Shabbat, or any of the other minutia of Jewish practice that give it depth. So, if you want a genuine Jewish heroine who on the surface seems to be the model of a particularist Jewish liberation struggle — but actually isn’t — then Esther is a great choice.

What I love about Judaism though, is that for the most part, that isn’t the model of liberation that we elevate. The central Jewish liberation story has our leader speaking truth against power, and the Jews finally being liberated from under that power. That’s Passover. We articulate that elohim y’vakesh et hanirdaf — God seeks those who are pursued, which we could read as “persecuted.” (Ecclesiastes 3:15) The model of the prophets, the 36 repetitions of “love the stranger,” and the choice about when we actually do say Hallel (Pesach, Chanukah, Sukkot — holidays that commemorate the terrifying freedom that comes when we break the status quo and set out on our own) all remind us that true liberation comes against totalitarian power, not by cozying up to it.

This is not to say that we shouldn’t celebrate Purim, God forbid! Purim is a farce — it reminds us to mock those who abuse power, those who invent a kind of safety by creating internal enemies. It reminds us that even when things seem very bleak, our ability to name the absurd and to respond with laughter is one of our greatest treasures. So let’s celebrate Purim this year, and take what celebrations we can, but let’s not confuse the illusion of safety with true liberation.

Rabbi Ruhi Sophia Motzkin Rubenstein has served as the lead rabbi of Temple Beth Israel: Center for Jewish Life in Eugene, Oregon, since her ordination from the Reconstructionist Rabbinical College in 2015. Prior to rabbinical training, she worked as a Jewish environmental educator with the Teva Learning Alliance and was a New Israel Fund-Shatil Social Justice Fellow. She grew up in Saratoga Springs and has studied and lived in Costa Rica and Jerusalem. Ruhi Sophia graduated from Smith College in 2007.

Her latest dvar will return soon.

View our archive of her past newsletter columns, her divrei Torah (sermons), and writings of former rabbis and other members of the TBI community.